Introduction

My efforts to research the genealogy of the families of my maternal ancestors began in the late 1930’s. At that time I gathered enough information to create basic charts of the family, intending to fill in details of the history itself at a later time. Subsequently, other interests entered my life and the genealogy lay dormant for many years. In the fall of 1976, I returned to the project and completed my research; this volume is the result.

In the course of my renewed search for long-lost relatives, I advertised several times in the Jewish Week, listing the relatives whom I was trying to locate. One elderly relative called, insulted. Why was her name in the ad, she demanded to know. “I have been in this country forty-nine years and have never been lost!”

Ultimately, this family history is about the importance of not losing family ties. It is about the value of Jewish traditions to the family, and to the larger society. My own interest in genealogy was aroused during my scholastic career, in the 1930’s, by my study of the links between family and tradition in Jewish history. The great contributions of the Jewish people to the moral, scientific, religious and educational development of the world in the last two thousand years have not been given the recognition they deserve in traditional non-Jewish histories and text-books. Symbolically, then, it seemed appropriate to create a history of one family, my own, and trace its links to the Jewish scene. Somehow I had the feeling that I would like to find in my family to the traditions of greatness in Jewish history.

This is the genealogy of the families of the maternal ancestors and their progeny. Specifically, it is the story of the families of:

Jacob Maier Tenzer, born 1837 (my great-grandfather)

Zisha Tenzer, born 1832 (Jacob’s brother)

Chana Henya Beer, born 1839 (Jacob’s sister)

Deborah Zahl Tenzer, born 1836 (Jacob’s wife)

Shalom Yonah Zahl, born 1792 (Deborah’s father)

Michael Tenzer, born 1869 (Jacob’s son; my grandfather)

Rose Bernstein Steier Tenzer, born 1869 (Michael’s wife; my grandmother)

Rachel Feiler Bernstein Steier, born 1847 (Rose’s mother)

At first I had intended to examine both my mother’s and my father’s families. But my father’s brothers and sister had come to the United States at an early age and virtually lost contact with their relatives abroad. Thus it was extremely difficult to trace that branch of the family back very far. With my mother’s family, facts were more readily available, and I was able to gather information without visiting Europe. Reluctantly, I decided to limit my work to the history of my mother’s family.

Researching just one family proved to be an arduous task in itself. Much information on the family was contributed by my older relatives, still alive in the 1930’s. These were my grandfather, Michael Tenzer, two of his older brothers, Meilech and Toivia, and other relatives who were contemporaries of theirs. They, together with those who came to the United States in the 1930’s and 1940’s and some American relatives who visited Galicia during this period, supplied me with the facts for my initial work on this family history. Many of these elders were born between 1850 and 1870 and remembered their grandparents, born fifty years earlier. The visitors to Galicia also brought me back information from family tombstones.

With all this information, I reconstructed the basic genealogy, and laid it out on two cardboard charts 44 inches by 64 inches. These spent almost 40 years in storage area, rolled up, but taken out from time to time to resolve questions in family discussions. I retained them, always intending to complete the family picture someday and publish the results.

Thus, when I finally resumed the project, in late 1976, it was with wholehearted enthusiasm. In order to complete the tree and fill in the blanks in our family history, I launched an all-out campaign. I made hundreds of phone calls over the world, visited government archives, searched telephone directories, examined tombstones, ran newspaper ads, visited relatives here and abroad, and enlisted the aid of others. It took persistence, and there were many false leads, but gradually I succeeded in tracing all but a very small segment of the family.

In addition to those listed here I traced about a dozen Tenzer families with which I was unable to show a definite link to our family. They are therefore not listed here, even though some came from the same towns and had similar first names.

One of these, Dr. Emanuel Tenzer’s grandfather, was Shimon or Solomon Tenzer, born 1851 in Nowy Sanz. Emanuel told me that they always thought they were related to our family. His family were musicians and doctors. Manny, his father Elias, and grandfather Shimon were violinists. Family tradition placed their ancestors of the Middle Ages in northeast Germany at the mouth of the Elbe and Weser Rivers. They are said to have been entertainers at the courts of the nobles.

This volume traces the lineage of my mother’s family, going back to Jacob Maier Tenzer’s great-great-grandfather, born 1690, and continuing up to November 1977. The genealogy spans ten generations, and includes some 1,500 persons, 161 of whom perished in the Nazi Holocaust.

A Brief History of the Family

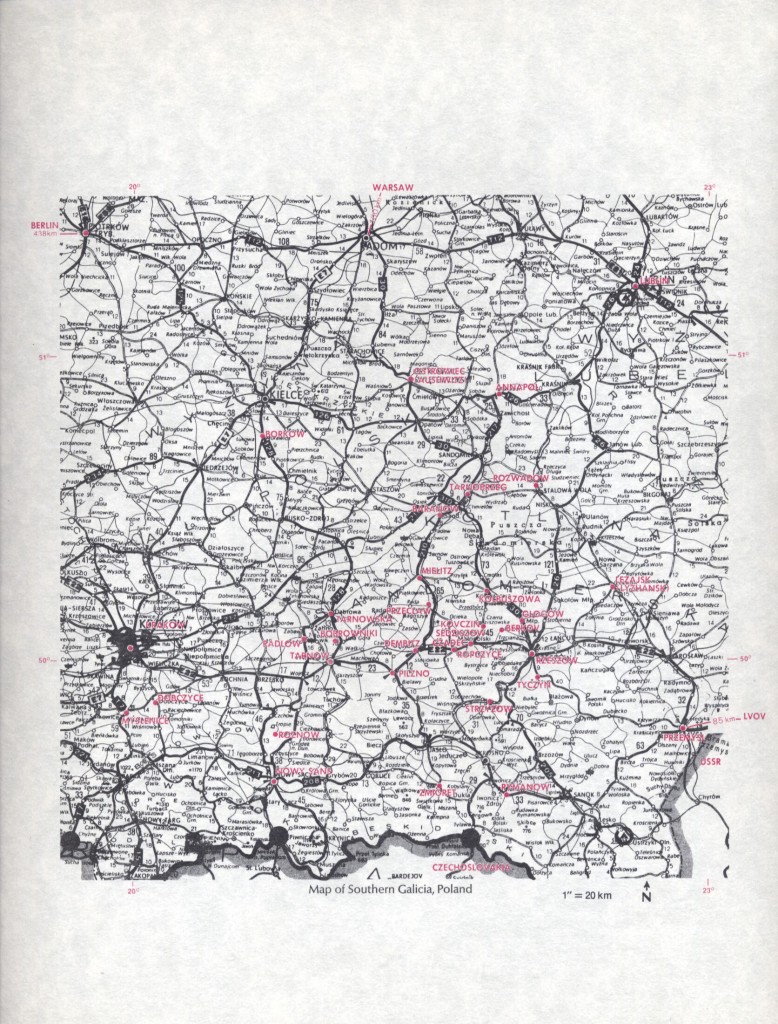

During the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the Tenzer family lived in southern Galicia. Some of the towns Tenzers lived in were dembitz, Kovczin, Sedzisow, Ropczyce, Mielitz, Baranow, Berkov, Zhmigret, Krakov, Bobovnik, Nowy Sanz, Glogow, and Tolna. Most family members are observant in their religious practices, and, especially in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, many were rabbis. Some were poor, many were prosperous- -as shopkeepers, bakers, farmers, millers, wine and lumber merchants, and traders.

A family scholar, Rabbi David Barbalatt (Plate 2), has worked on the origin of the name Tenzer. One of his theories is that Tenzer is a shortening of the name Forstenzer, which means “spokesmen”. He also suggests that the name may have come from the word for “Dancer”, a logical possibility since many Jews in the old days were forced to become entertainers to royalty because of the lack of other trades open to them.

One of the earliest known ancestors of the Tenzer family was Rabbi Shlomo Zalmen ben Maier (Plate 1), born in 1720. Many a wondrous deed has been attributed to this man, known as Reb Shlomo the Chusid, the Wonder Rabbi of Glogow. Tales of his actions has been handed down through the generations, and the people still speak of him in awe. Shlomo had five disciples, among them the Robczycer Rav, Usher Horowitz; the Fristiker Rav, Der Shach; and the Strizhever Rav, Shlomo Zalman Tenzer (born 1765) This last disciple, Shlomo Zalmen Tenzer, married his master’s daughter, Hinda Chiah.

According to Rabbi Meyer Horowitz, a genealogist in Brooklyn, Shlomo Zalmen was the student of Rabbi Jacob Yitzhak Horowitz of Lublin, the outstanding Hasidic rabbi of the time, who died in 1815.

The story goes that one day Rabbi Shlomo Zalmen went to Lublin, arriving in the middle of the week, and went to synagogue. There a man stood at the omad to daven, and fainted. Another man rose to take his place, but he, too, fainted as he began to daven. A third rose, davened, and fainted. At this point the rabbi of the synagogue said, “Send for the Robczycer Rav.” The Robczycer arrived, started to daven, then to perspire, and he fainted as well.

Finally Shlomo Zalmen was called. Shlomo began to daven. When he came to the Baruch Choo he held the rails and trembled, and perspired. He perspired so profusely that they brought towels in to wrap him up. But he finished his prayers. Afterward the rabbi asked Shlomo what had happened. Shlomo said the Tzelem had stopped him. “Where are they?“ “Bring shovels and I will show you.” They brought shovels and dug in the courtyard and found crosses wherever Shlomo Zalmen pointed to the ground. The crosses had made the davening trefe.

In another story, Rabbi Shlomo Zalmen and the Robczycer Rav were in Lublin for Shabbat with Reb Choyseh. There they davened with five thousand Hasidim. After the service they went to Reb Choyseh’s home and waited for kiddish before lunch. Reb Choyseh delayed making kiddish. Two or three rabbis stepped up to him and said, “Let’s make kiddish. It‘s getting late.” Reb Choyseh finally replied, “I’ll make kiddish when you bring Moske before me.” Moske was a wealthy man in town who was a mitnaggedim (opponent) of the Hasidic movement. The assemblage pondered. Who could possibly arrange for Moske to be brought to Reb Choyseh when he had refused so many times?

It was decided that the only one who could do it was Shlomo Zalmen. So Shlomo went to Moske. Moske had been studying Rambam and had a problem he couldn’t answer.

He had sent all over Poland for the answer without any results. When he learned of Shlomo Zalmen’s mission, he said, “If you can answer this problem, I will go with you to Reb Choyseh.” Shlomo thought a moment and delivered the answer. Moske was stunned. “How did you arrive at the answer?” he said. Shlomo replied, “The Rambamstood in back of me and answered.”

Moske went with him to Reb Choyseh. A third story concerns the grave of Shlomo Zalmen. This grave became a revered memorial visited by many disciples, especially on the anniversary of his death. As time went by, the grave grew higher and higher, and soon a cherry tree grew out of the grave. It was a holy spot, one of the untouchables. One night a poor woman went to pick cherries from the tree. Suddenly a hand emerged from the grave and struck her on the hand for her deed. The mark of the grave’s hand stayed on the woman’s hand all of her life.

All three of the above stories were told to Stanley Batkin by Jack Tenzer, who had heard them from Isak Beer, who had in turn been told the stories by his mother, Chana Henya. Shlomo Zalmen was Chana Henya’s great—grandfather.

Shlomo Zalmen’s tombstone reads:

Shlomo son of Maier.

Shlomo died and is gathered to his people.

He was a rabbi, a pious man, son of Rabbi Maier,

A chain of nobility descending from Rashi.

Died 16 days, Menachem-Av 5,543 (1783).

He was called Shlomo the Chusid.

The oldest child of Shlomo Zalmen Tenzer and Hinda Chiah was Elimelech, born in 18ll.

At the age of six or seven, the boy was kidnapped by a merchant from a distant town and put to work for him. The lad, however, apparently undaunted, worked hard, saved his money——amassing the sum of two hundred gold rendlach—-and ultimately made his way back to his hometown of Kovczin, about a quarter of a mile from Sedziszow. There he bought a bar and prospered. (His first wife Rebecca died and there is no trace of any children.)

Elimelech’s second wife, Breindl, had been married previously and had two daughters and a son by her first husband.

Breindl and Elimelech together had three children: Jacob, Zisha and Chana Henya. The youngest was Chana Henya (Plate 16), born 1839.

Chana married Moses Beer of Dembitz.

Moses was a wholesaler in flour, wheat, and corn, and the couple lived quite comfortably in Dembitz.

Chana, physically a large woman, was a very clever and warm, kind person, and was cherished by those who knew her.

Chana’s grandson, Dr. Yaakov Beer, remembers her, from the age of seventy-four to her death at eighty-two, as an involved and dedicated woman. She was most intelligent, and was respected by everyone; her purpose in life was to help others. She was called the Mother of the Jewish orphans, for her work with that group of people.

She always made a special point of making their engagement parties and weddings. Chana was an outstanding cook; some of her cake recipes are still followed to this day by her descendants.

Almost one-third of Chana and Moses’ descendants perished in the Holocaust. The remainder of the family is spread throughout France, Israel, South America, and the United States.

Jacob Maier Tenzer, the second child, born in 1837 (Plates 8 through 15), was a Talmid Chucham, a learned man, a pious Chusid. He was strong, quiet, and known for his wisdom and reflective ness. He was also proud, a natty dresser, with boots always shined, and a pipe smoker. Jacob lived on a farm in Kovczin. Half of his farmhouse was used as his living quarters, and the other half housed a store, where he sold groceries and supplies to farmers.

Deborah Zahl Tenzer, according to the late Sidney Herbst, who knew her, was a tomboy when she was young, and could outskate any young man in town. She was also well known for her keen wit and ready speech, and for her Hebrew learning – she could recite the entire Hebrew prayer book from memory. She grew into a tall, slender, agile, blue-eyed, blonde young woman.

Deborah was the second of four daughters of Shalom Yonah Zahl (Plate 23), the pious cantor and shochet of Robczyce and Sedziszow. When they grew to maturity, Deborah and her sister, Gladys, remained in Sedziszow. Marion settled in Tarnow, and Hannah married Joel Morgenbesser and sailed to America.

At the age of nineteen, Deborah married my great-grandfather Jacob Maier Tenzer. Jacob and Deborah were opposites who complemented each other, and their life together was a happy one. She was frail and dainty; he was strong and patronizing. She was clever and keen; he was wise and slow in decision. She was temperamental; he was quiet. Deborah often made up her proud husband’s mind without his knowing it – or at least without his letting on that he knew it. She was a clever woman, the actual manager of the household. It was her magnetic personality that drew the whole family to their house for weekly meetings the year round during their lifetimes.

Deborah and Jacob had large farmlands, where they grew wheat, corn, and potatoes and raised cows and horses; they also had a flourmill. On the Sabbath, Deborah wore a Sterntichel, a headdress consisting of a silk cap with a tiara in front studded with pearls and semiprecious stones. She looked regal.

Deborah had a beautiful smile, a warm personality, and a tremendous love for her children and grandchildren. In times of affliction, she was calm, unflinching and heroic. Having been brought up in a deeply religious atmosphere, she accepted punishment from Heaven as her just due. One of her favorite sayings was, “Well, are we to tell Him how to manage the world?”

Deborah’s father, Shalom Yonah, and the Riglitzer Rav, who was a Tenzer, had both written the lineages of their families back to King David. This was not as difficult as it might seem, since the lineage from Rashi in the twelfth century to King David had already been established.

Zisha Tenzer, the third child of Breindl and Elimelech, was born in 1832, and lived in Kovczin as an adult (Plates 2 through 7).

He operated a bar, probably inherited from his father, who died when Zisha was thirty-four.

Zisha was some type of banker and accumulated wealth. He was kind and hospitable, and visiting members of the family were always welcome to stay at his home. Zisha and his wife, Esther, were very religious.

Their granddaughter Ethel Jacobs, daughter of Sarah and Moses Raab, remembers a few visits they made to their home in Baranow where they attended religious services.

Life in Galicia was often difficult. There was little opportunity to expand family enterprises, and anti-Semitism was widespread among the Polish peasants, the Jewish shopkeepers’ main customers. It was partly in response to these factors, then, that in the early nineteenth century the Tenzers began to migrate westward. Some stopped in Hungary, Germany, and France, but most pushed on to the goldeneh medina, America especially in the years 1850 to 1930.

One of these new immigrants to America was Michael Tenzer (Plate 13) who ran away from home in 1883 at the age of fourteen, and arrived in New York two months later. Before departing, Michael left a sealed note to his parents on Friday before sundown. The note, which could not be opened until Saturday evening, told of his plans and asked for their blessing and forgiveness.

Michael Tenzer’s life from then on is a Horatio Alger story. Arriving in the United States as a young adolescent with four dollars in his pocket, he began buying and selling notions, traveling to New Jersey and Pennsylvania with a pack on his back. Through hard work, he prospered, and in a short time he was able to open a candy stand, then a store, and finally he became a wholesale confectioner, eventually the largest in New York City.

Several years after his arrival in New York, Michael roomed with the Steier family. Soon, romance blossomed with pretty Rose Steier, and the couple was married in 1890.

A loyal Jew and a dedicated American, Michael Tenzer was also a humanitarian and a philanthropist whose advice was often sought. He frequently loaned money to friends, always without interest, and gave money to the needy. Though an ambitious and successful businessman in his own right, he once loaned Milton Hershey one thousand dollars to start making chocolate bars, turning down a partnership in the Hershey Chocolate Company.

Michael was an early client of William Wrigley, George Loft, and others. He acquired real estate on the lower East Side and lower Manhattan, including holdings on Broome, Essex, Montgomery, and Clinton Streets. He owned the Metropolitan Theatre on Essex Street. Michael bought a farm in Pine Brook, New Jersey and organized a synagogue and family cemetery there. He also founded the great Yeshiva Talmud Torah of Crown Heights in Brooklyn.

Michael Tenzer was an inspiration to his family, friends and associates. A man who could be stern, strict and sometimes obstinate, he was a leader and dominant character. Family was of the utmost importance to him. In 1927 Michael and his children founded a family organization, the Michael Tenzer Family Circle, Inc. The Circle has been a source of family strength and cohesiveness since its beginnings, and its meetings contribute to a sense of family charity, purchased family cemetery plots, aided the less fortunate members of the family, assisted family members in Europe during the Holocaust and provided packages to those family members serving in the US Armed Forces. In June 1977 the Circle celebrated its fiftieth anniversary with a dinner in New York City attended by over 175 members.

Michael, who doted on his grandchildren, used to entertain them with a “Chinese” song sung in his version of the accent, inspired by his Chinese neighbors on the Lower East Side. He also introduced all the children and grandchildren to arithmetic with his chant, “Onezer, twozer, threezer,….ninzer Tenzer”, which ended in cheers and applause.

Michael’s wife, Rose, was a good-natured and considerate wife and mother, a wonderful housekeeper, cook and organizer. Over the years, she always lent an ear to the problems of the children and grandchildren, and was helpful to all who came to her for aid. In her later years, Rose baked individual challahs for my children who were her great-grandchildren. A warm affectionate, and self-reliant woman, Rose was well liked and made lifelong friends with her neighbors.

Rose was unschooled, and could not read or write—the children taught her to sign her name. She worked in her husband’s business at the cash register. As the business prospered, Rose, who had come from such humble beginnings, eventually had two servants at home. She was gentle and a dignified woman who never raised her voice except to quiet the children when they were disturbing her husband. The strong and dominant Michael did not tolerate smoking by women: so Rose cautioned the women to open the window in the bathroom when they smoked there.

The Tenzer home was a haven for family immigrants from Europe; they would come right from the boat and stay for a month to a year until they were ready to launch their own careers in America. Both Tenzers were known for their kindness to those who were still struggling. In Jerusalem in 1977, I met a retired businessman, Sam Cummings, who told me the story of his business career. He had gotten started as a boy of eleven, “selling penny candy on a corner on the East Side of New York. I had no capital, but there was this nice woman on Broome Street, the wife of a wholesaler jobber. She said, “Go and do business, I’ll trust you.” I owe my success to that woman” That woman of course was my grandmother, Rose Tenzer.

Rose’s parents were Rachel Feiler and Jacob Steier (Plate 17). Rachel, who was a gay, kind person, was widowed at a young age with two children, Blem and Rose. Jacob Steier was her second husband. The two together with their six children made their way from Krakow to the New World in 1887. There Jacob made a meager living from a stand on Ridge and Houston Streets in New York, where he sold milk glass, pottery and other kitchenware. Rachel would bring lunch to the stand every day. She and the children supplemented Jacob’s earnings by doing housework.

Rachel, who was quite religious, always wore a scarf on her head. Over her dress she wore a long calico apron. She spoke only Yiddish and Polish refusing to speak English. Rachel was an excellent cook and baker and her culinary arts were handed down to her children and family. Her specialties were an old-fashioned coffee cake and rugaleh. Her daughter Blema would run a restaurant until the age of ninety and may of progeny were and still are in the food business. Rachel loved her children and grandchildren; Bertha Tenser was her favorite grandchild. Rachel’s brother, Moshe Feiler, was an inspector of the Krakow police department.

The early Tenzer immigrants frequently began their business careers in America as peddlers, and sometimes as storekeepers. They worked hard, prospered, sent their children through high school, and enlarged their businesses, with their aid of their children. The generation that entered the work force during the 1920s, ‘30s and ‘40s generally entered family businesses, and many became leaders in industry and commerce. A small percentage became professionals and made substantial contributions to the fields of medicine and law.

In the 1950s, ‘60s and 70s, society at large witnessed an increase of mergers and the concentration of industry in large corporations, and consequently fewer opportunities in family businesses. This was reflected in the Tenzer family as well. During these years, there was a great increase in those achieving higher education. More of our youth became highly qualified, technically oriented jobholders in large corporations or became professors, doctors, computer specialists, lawyers, bankers or judges.

Physically, the Tenzers look much like other Ashkenazic Jews. They have tended to be shorter than average in height and fair in complexion. However, their average life expectancy has been considerably greater than that of most people in the areas they have inhabited. The children of Jacob Maier Tenzer, with the exception of one who died early, lived an average of seventy-five years. Jacob’s brother Zisha Tenzer’s children averaged about the same. Their sister Chana Henya’s children averaged only fifty-eight years, perhaps as a result of an unusually high frequency of breast cancer. The next generation of the Tenzers continued to have a normal life span well beyond the average. The Tenzer family has more than the usual number of twin births.

The research showed a large percentage of professionals, concentrated higher divorce rates in certain families, higher proportion of unmarried people in some families and specific illnesses handed down through the generations. The family in Europe were Orthodox Jews. Those who came to this country after World War I have tended to retain their religious observance more than those who arrived prior to the war. Some families are very close knit; in others, people were unknown to their first cousins and even brothers.

By the 1970s, the Tenzer family had spread to South Africa, Israel, France, England, Canada, South America and twenty states in this country. During my research in the last year I had hundreds of meetings and thousands of conversations with family members. For me it was deeply rewarding and at times exhilarating experience. For those who were “discovered” it was often a joyous occasion. In many cases, my work put cousins in touch with each other for the first time in their lives. In the process of re-creating our family. we made contact with many Tenzers who could not be connected with us; their regret at the lack of family connection reinforced my sense of how important this work had been.

If family history is reviewed and renewed by each succeeding generation it can be a source of security and of a sense of continuity. It can bind one generation to another, draw individuals within a generation closer. It can provide an answer to the yearnings of youth and elderly for knowledge that they belong. When a sense of one’s own Jewish tradition and family ties are strong, youth do not need to seek out new superficial cults to sustain them. With a sense of one’s own past, the present holds no fear and the future can be an inspiration on which to build a life.

The Jewish tradition is a treasure, and the family its stronghold. Let us explore, cherish and strengthen our family bonds.

Stanley I. Batkin

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Special thanks to:

Harold Warshow, who graciously and artistically set all the typography and made all the layouts for this publication;

Kathie Gordon who was my copy editor;

Clare Pollard, my secretary for her assistance;

Jennie Katz for her research on the Feiler family;

Universal Folding Box Co., Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey, whose Partners, Sanford L.Batkin and Stanley I. Batkin, contributed in the printing and publication of this journal.

I have attempted to be as thorough as possible in this work and apologize for any errors and omissions; responsibility for these, of course, is the author’s alone.

To all whose information and assistance made this book possible, I express my sincere appreciation.